Thanks to B. Hendrickx and Flyback for reviewing this article.

In the first article in this series on finding out what options Russia has for using nuclear power in order to counter satellite constellations, we reviewed the country’s two space nuclear reactors programs, and compared them to the simpler option of just using very large solar panels. Both options can provide hundreds of kilowatts of electrical power. Now we will look into a first way to put this power to use.

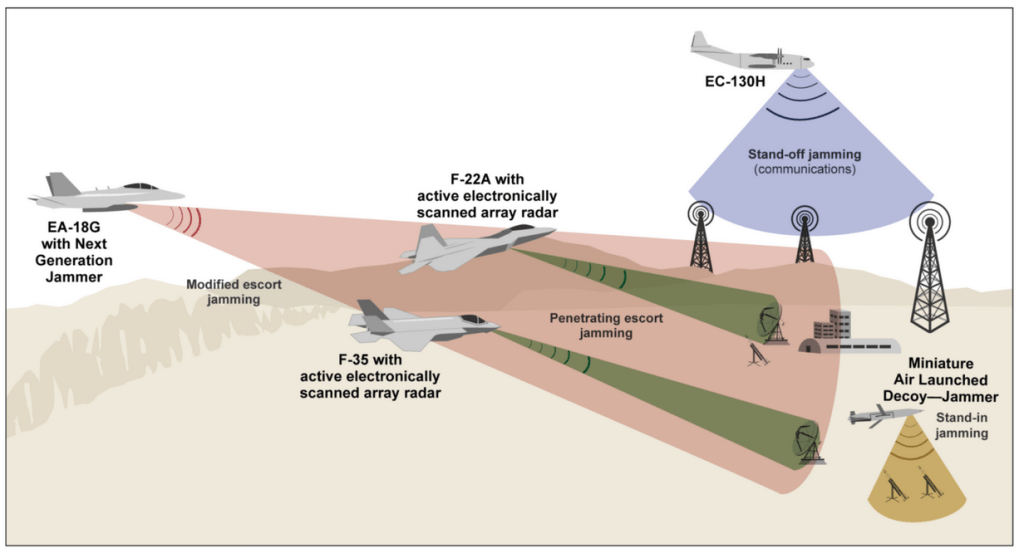

If you have a lot of electrical power and want to interfere with enemy operations, the first thing you think about is a jammer. The Russian have seriously considered putting a jammer on a nuclear-powered satellite, as Bart Hendrickx has brilliantly shown through his intelligence work on Ekipazh.

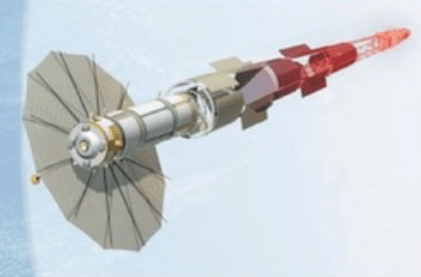

The uncovered documents describe designs for electronic warfare satellite with a power of 30 to 50 kW, and also presented a plan at some point to use the TEM with an electronic warfare payload, under a project called Yadro (core). The antenna for this would be 10 x 2.5 x 0.4 meters folded, so should reach around 20 meters unfolded at least. However, just because they considered it does not mean it was serious. Yadro was kind of a solution looking for a problem, trying to find applications for the power of the TEM beyond a space tug or a solar system probe. They also looked into using for a space-based radar, for laser power beaming, for communications, and for moon base logistics.

There are good arguments against putting a jammer in space, centering around the increased distance to the target compared to a conventional ground or airborne jammer, the technical difficulty of generating high power in space, and the near impossibility of putting a satellite in the main beam of the target and having it stay there. Let’s look into this in more detail.

Space-to-ground jamming

First we consider space-based jamming against a surface radar or communication system (excluding satellite communications):

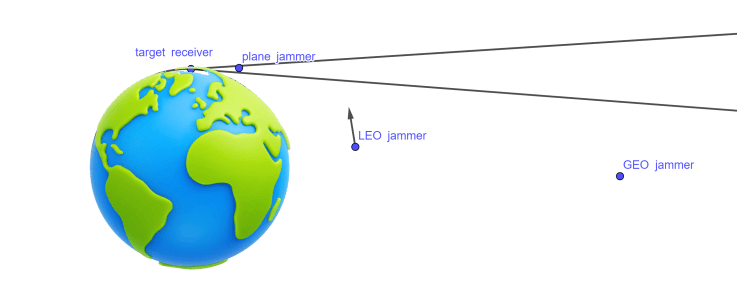

In this (not to scale) diagram, we have a conventional airborne jammer, a jammer on a Low Earth Orbit satellite, and a jammer in geostationary orbit (GEO), all trying to attack the same target receiver on the ground. This receiver is directional, and the cone going out to the right is its main lobe (which can be quite tight for radars). This beam is typically pointed at the horizon for radars, so an airborne jammer can be maneuvered to sit inside it and stay there. It is also true for a ground-based jammer if it can get close enough to the target.

The LEO satellite, however, is constrained by orbital mechanics. It will not pass through the beam at every orbit, and when it does it will be there only for a short time. Jamming has no permanent effect, so as soon as the jammer leaves the beam the target will recover nominal performance. Another downside compared to the ground jammer is the increased distance. Jamming effectiveness degrades with the square of the distance. For a LEO jammer, an optimistic distance to the target in a good pass is at least 1000 km. Compared to an airborne jammer flying 100 km away, that’s already a 100x performance hit.

The problem of distance is worse in GEO, even though in the diagram we are in an favourable case and the main beam crosses the GEO belt, so the jammer can stay on target all the time. At 36 000km of distance, we have a reduction in jammer effectiveness of 130 000x compared to the airborne jammer. That means a 1 MW jammer carried by a TEM would be as effective as a 8 W airborne jammer with the same antenna. The space jammer can partially compensate for that by having a larger antenna than what can be mounted on the plane, but even using a 20m diameter antenna versus a 1m antenna on the plane, distance makes the satellite jammer equivalent to a 2 kW jammer on a plane, which is still not a lot. Legacy jamming pods carried aboard fighters like the ALQ-99 radiate 6 kW of power, while the next generation ones promise an order of magnitude improvement. Dedicated jammer planes can have larger antennas and more power.

That is assuming that the GEO jammer can be put in the beam when the beam is in a tactically relevant direction. So overall, this kind of jamming is not the most promising, especially close to frontlines where an airborne jammer could be used.

Jamming communications by satellite

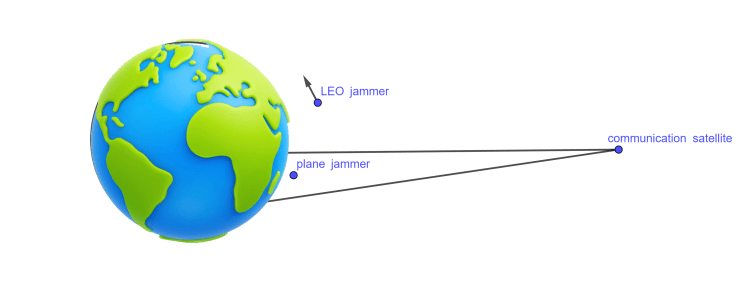

Jamming the ground terminals of LEO communications constellations like Starlink works pretty much in the same way as described above. The terminal points a beam at the satellites it can see. The beam is however not pointed at the horizon and is constantly moving, so it is complicated to place a ground or airborne jammer inside it. But it is also complicated to keep a LEO or GEO jammer within it.

Some ground terminals have non-directional antennas, especially for hand-held use, but even in this case there is a 1200x penalty due to distance when comparing a GEO jammer and a communication satellite passing 1000km away from the user. Such satellites, like the Iridium Next ones, have 1 kW of average electrical power and radiate towards the ground a fraction of that. So a 1 MW GEO jammer could locally overpower them for users with the smallest terminals.

A different case occurs when the ground terminal listens to a GEO communication satellite:

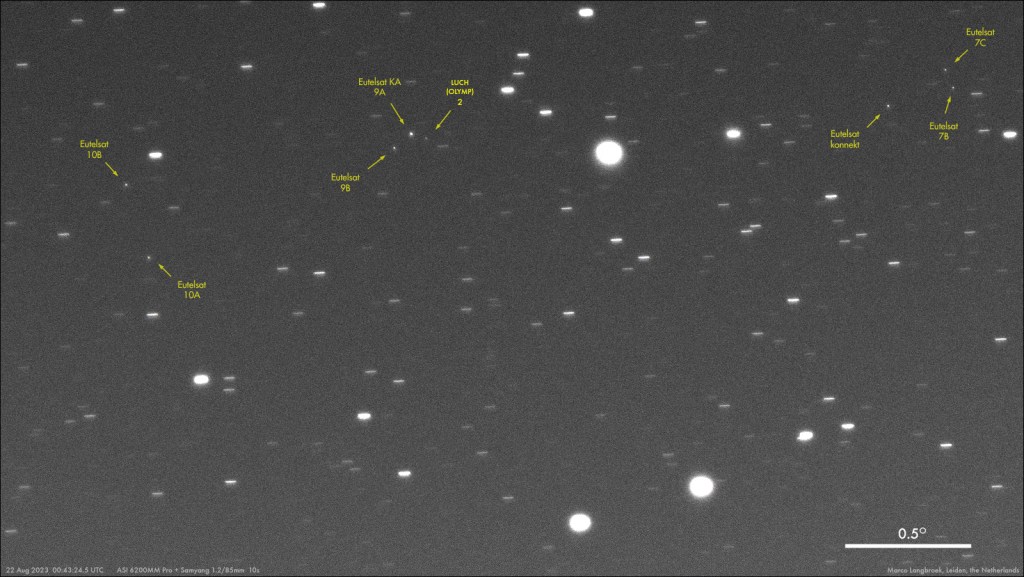

Here, the beam of the terminal is fixed, and pointed at GEO. So it is easy to maneuver a GEO jammer into it, by putting it next to the legitimate emitter. As a bonus, this emitter has its signal attenuated by the distance to Earth as much as the jammer’s. Russia is quite familiar with this kind of proximity operations, as it has operated since 2014 the Luch-Olymp eavesdropping satellite, which liked to hang around communication satellites in GEO, and has recently launched what appears to be a replacement for it:

This is the best application for a jammer satellite. However, a nuclear-powered satellite is not required for that. Any standard GEO communication satellite can be turned into a jammer equally powerful as the legitimate satellite, by changing its frequency so that it emits on the frequency used by the target instead of a separate one. The jammer even has a further advantage in that it can choose to jam a specific region, whereas the communication satellite generally has to spread its signal over a much wider area: Russia could use a jammer to target only Ukraine for instance, without dedicating power to other areas it cares less about. A caveat is that some communication satellites can concentrate their power in spot beams over zones of interest, and so could fight head-to-head with the jammer.

GEO satellites use less than 20 kW of power, much less than the hundreds of kW of the nuclear reactor projects. Where additional power might be useful for the jammer is against military communication satellites, which have features such as frequency-hopping forcing the attacker to jam more frequencies than what the communication satellite actually uses, resulting in an advantage for the defense.

The extra power of a nuclear satellite might be interesting to jam without having to be in the main beam. That allows more flexibility, and even to impact the users of multiple satellites, by jamming multiple frequency bands, which requires more power than just one. It would probably done preferentially for lower frequencies, where the beams are wider.

Jamming in the other direction, meaning affecting the uplink of the communication satellite rather than its downlink, is much harder if done from LEO:

Space-to-Space jamming

A last use case for jamming could be to jam the command and control of satellites. Usually, those are transmitted from a ground station to the satellite, which receives it on a non-directional antenna, so that it works even if the spacecraft is in a non-nominal attitude. If that link is jammed each time the satellite expects to receive inputs from a ground station, it will probably just stop its mission. Even if it carries on the mission with a fall-back plan, this will not last very long, especially for satellites requiring agile tasking. This attack can be done either from GEO against a whole constellation, by illuminating satellites passing over ground stations, or against a single target by following them in a co-orbital manner, but in the latter case a small satellite getting very close does the job just as well as a nuclear-powered monstrosity. In a similar manner, the GPS receivers present on satellites could be attacked, but to be effective the jamming would probably have to be almost permanent.

However, modern constellations usually feature inter-satellite links which could be used to transfer the commands, and can use higher-frequency directional control-command links. The US military constellation will use Ka-band TT&C links for instance. Such constellation can also provide their own embedded position and timing services, without relying on GPS.

Counter-countermeasures against jamming

Detecting and attributing jamming attacks is relatively easy to do: finding the source of jamming just means find the direction it comes from. If that matches a suspicious Russian satellite, the culprit is found. Defending against it is a bit harder. There are ways to do it, like using hardened radio modes such as frequency-hopping or direct spread-spectrum, and generalizing phased-array receivers with steerable nulls. But for small, omnidirectional antennas, the latter is not possible.

Conclusion on jammers

Overall, the most likely use for a space-based jammer is to put it in GEO and point it at the Earth to disturb the GEO satellite communications users. With enough power, the users of multiple satellites could be affected, even those that are positioned quite far apart on the GEO belt.

In the next article, we will deal with more far-fetched concepts using directed energy.

[…] especially their military low Earth orbit constellation currently being launched. We will review jamming and then directed energy applications: High Power Microwave, Neutral Particle Beams and lasers. […]

LikeLike

[…] With great power comes great jamming opportunities. But in what cases does the increased difficulty of doing it from space outweigh the advantages? — Read on satelliteobservation.net/2024/03/13/countering-constellations-jamming/ […]

LikeLike

The more likely attack is low-power jamming by a co-orbiting antisatellite weapon, cutting off the up- or cross-link. Such activity could not be carried out covertly, but a big power might do this overtly as signaling in a (very serious) crisis.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed, there are Chinese research articles on that for GEO. However it does not scale well to a LEO constellation.

LikeLike

The ultimate futuristic counter-jamming technique is to not rely on a transmission medium at all–quantum entanglement could make it possible to directly control satellites and other space systems, although it may take decades to achieve.

LikeLike

You can’t send information though entanglement. Optical links exist and are very good against jamming.

LikeLike

[…] the large electrical power provided by a lighweight nuclear reactor the Russians could develop a jammer satellite able to severely degrade communications going through geostationary satellites. However, its […]

LikeLike

[…] option: putting a lightweight nuclear reactor on a spacecraft, to power either an electromagnetic jammer, or a directed energy weapon. Jamming is the softest scenario, in that after the jammer is turned […]

LikeLike