This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Disasters Charter, and CNES – the French space agency – decided to celebrate a bit early by giving a presentation of its activities within this framework. The agency held an informal session in a crowded parisian café to present its role and the one of its partners.

The speakers were Émilie Bronner, CNES’ representative at the Charter’s executive secretariat, and Stéphanie Battiston, deputy lead of the SERTIT emergency mapping service. They started by describing the history of the Charter: it was proposed in 1999 jointly by CNES and ESA, and the Canadian Space Agency instantly joined the project, leading to an official creation in September 2000. Today, there are 17 members, including national agencies (like NOAA in the USA) and international agencies (like ESA). They collect, analyze and distribute satellite imagery free of charge to any country that requests it following a natural or man-made disaster.

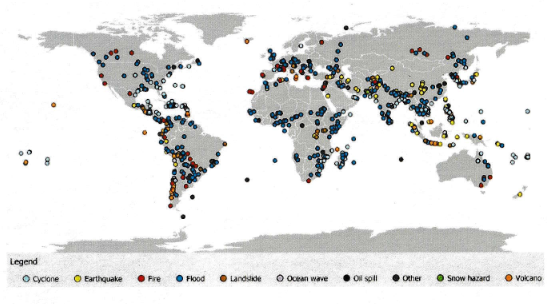

Some statistics were given to illustrate: in 25 years, there has been 950 activations of the Charter in 142 countries. In recent years, the numbers of activations has increased, going from around 40 a year in the 2010s to 50+ in the 2020s, with 2024 even reaching 85 activations! A breakdown by category reveals that half of them are for floods, around 30% for fires, landslides and storms, and the remaining 10 % for volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and tsunamis. That means that 90% are sensitive to climate change, and it might be the reason behind the recent increase.

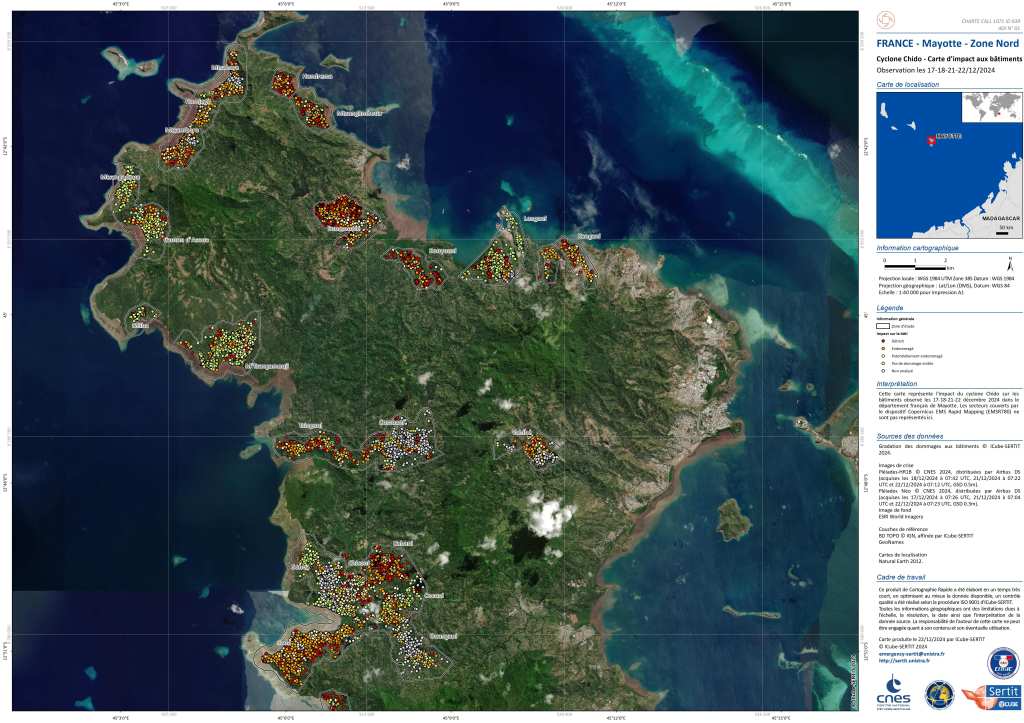

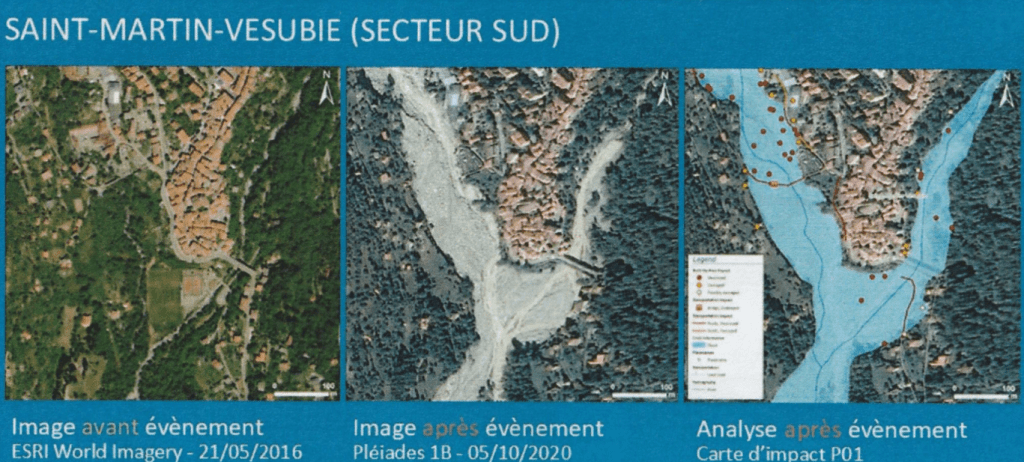

The activation workflow is that each countries has agencies that can declare an emergency by filling out a simple form, which is received by a charter officer on-call 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The request is then dispatched to the member agencies, and even to some commercial satellite operators that have agreed to help with the charter. The agencies task their satellites, receive the data in 24 hours or less, and then send it to an emergency mapping service like SERTIT. There, the raw pixels are turned into value-added products, by creating maps showing information directly actionable by first responders, such as the location of damaged building and the severity of the damage, which roads are no longer useable, where people are gathered following the disasters, the extent of flooding or fires, and so on. This is done mostly by image interpreters, with some algorithms being used to delineate flood extent, and newer AI algorithms slowing being introduced. All those products are available for free and posted on the charter’s website, disasterscharter.org .

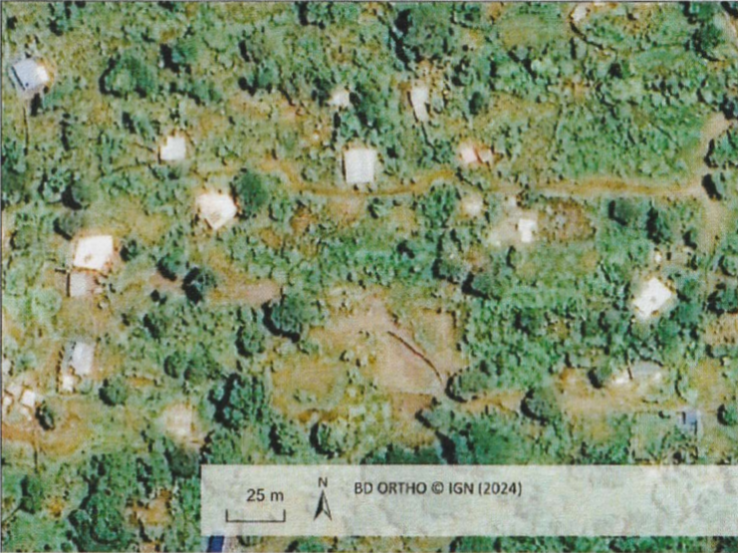

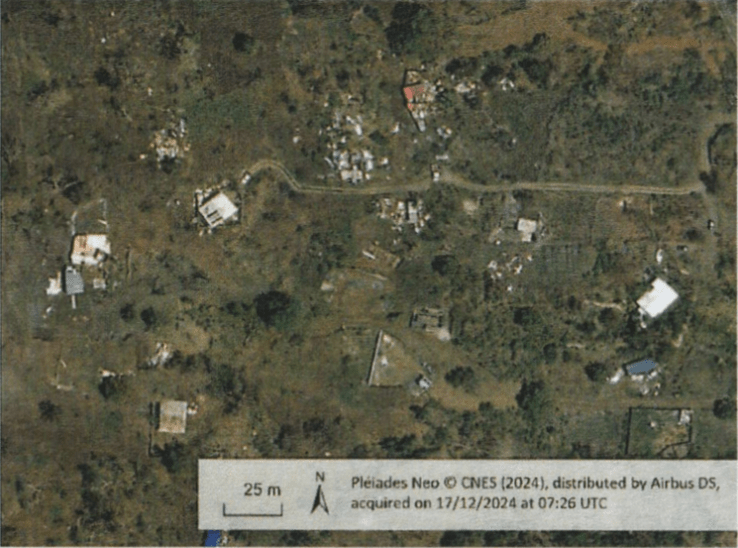

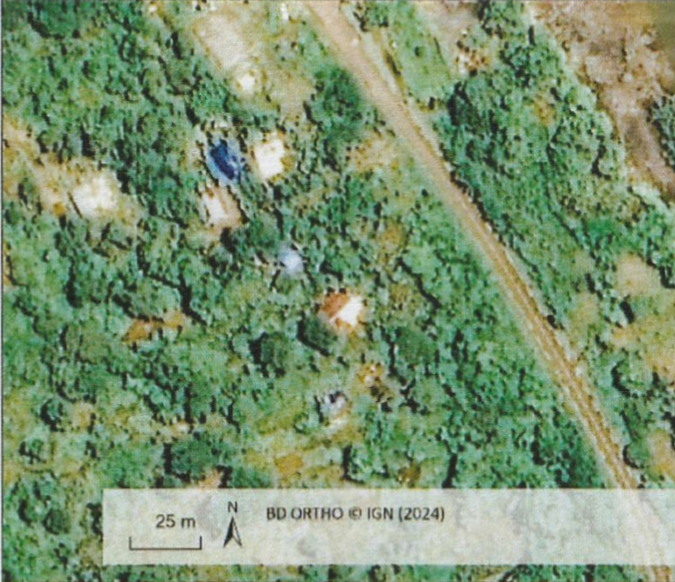

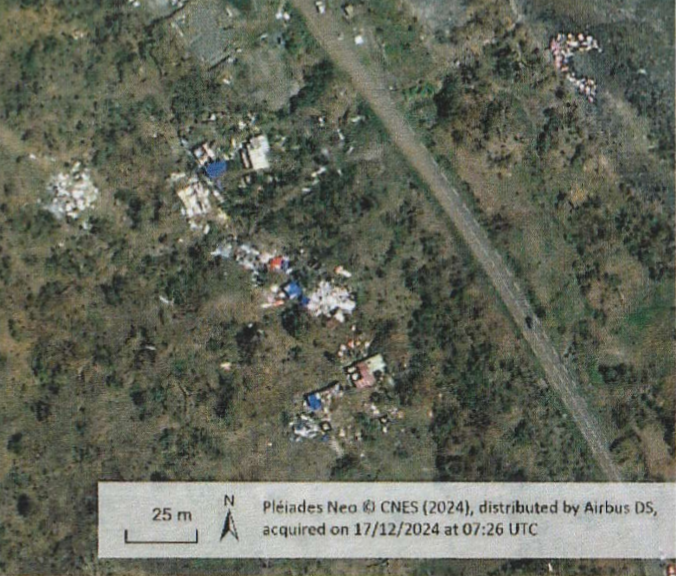

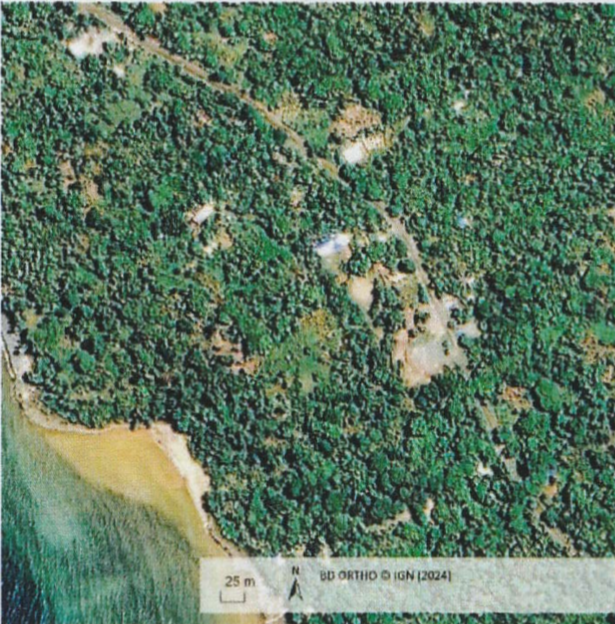

Mayotte Island, before and after cyclone Chido

In total, up to 270 satellites can be enrolled to collect imagery. This covers both optical and radar (SAR) satellites. High-resolution optical (30 to 50cm resolution) is preferred to estimate damage to buildings, but the area that can be collected is limited, meaning that the agency requesting an activation must communicate precisely which are the areas most affected by the disaster. Medium-resolution optical is then used to fill the gaps in the other areas. However, optical imagery has two drawbacks: first, it does not work at night since almost none of them has a thermal infrared capability, and second it does not see through clouds. This is a problem as most disaster events, such as floods, storms or landslides are associated with a strong cloud cover. Consequently, some data take opportunities are not exploitable, but it is possible to task many optical satellites to take images at different times and hope to see the ground through a gap in the clouds. In the case of the Chido cyclone which hit the island of Mayotte in December 2024, it took one week to map out all the island due to the poor weather.

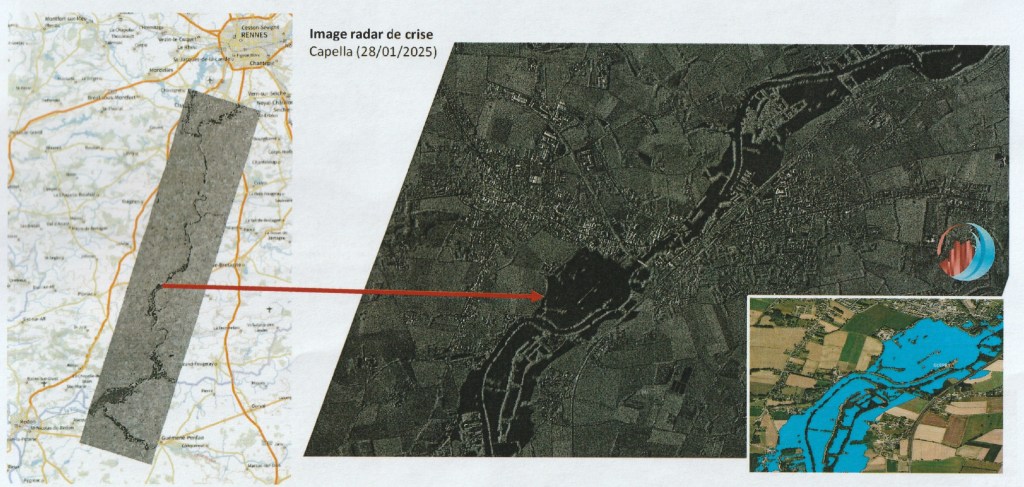

Radar, on the other hand, is very well suited to the flood case, since water is very easy to detect in SAR images: it appears as a featureless deep back surface, allowing accurate automatic extraction. That does not work for flash floods however, when the water rises and retreats extremely quickly.

A typical Charter product looks like this, here with a map of building destroyed or damaged by cyclone Chido.:

The Charter only addresses natural or technological disasters: other man-made disasters such as wars are excluded. This keeps the organization apolitical, which is necessary for images and resources to be shared between competitors or adversaries.

With the introduction of higher-resolution satellites, 30cm resolution becoming the standard at the highest end for optical, the entry of many new actors on the commercial imagery market, and the rise of constellations providing high-revisit capabilities, the Charter is set to become an ever-more useful tool to help first responders save lives.